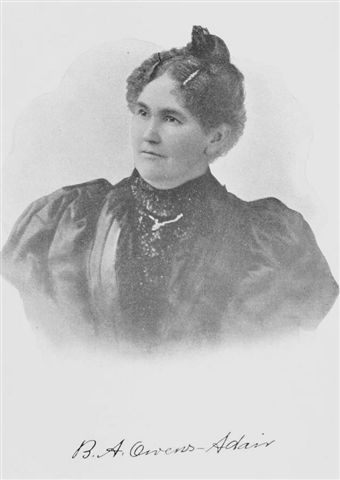

(The portrait on the left was published with this biography in "The Centennial History." The portrait on the right was published in her autobiography, "A Souvenir", in 1922.)

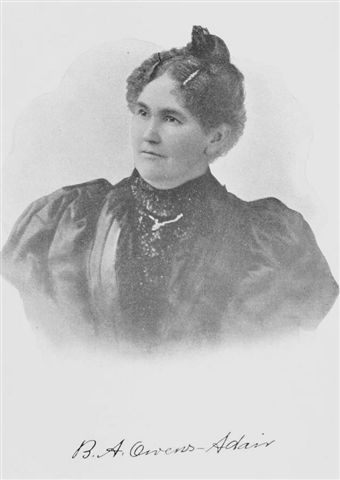

(The portrait on the left was published with this biography in "The Centennial History." The portrait on the right was published in her autobiography, "A Souvenir", in 1922.)

Gaston, Joseph. "The Centennial History of Oregon, 1811 - 1912." Vol. 4. Chicago, S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1912. p. 580.

DR. B. A. OWENS-ADAIR (Autobiographical)

I was born February 7, 1840, in Van Buren county, Missouri, second daughter of Thomas and Sarah Damron Owens. My father and mother crossed the plains with the first emigrant wagons of 1843, and settled on Clatsop plains, Clatsop county, Oregon, near the mouth of the great Columbia "River of the West," within the ceaseless roar of the mighty Pacific. I was then very small and delicate in stature and of a highly nervous sensitive nature and yet I possessed a strong and vigorous constitution, and a most wonderful endurance and recuperative powers. These qualities were inherited not only from my parents but my grandparents as well. My grandfather Owens was a man of exceptional financial ability. He owned a large plantation in Kentucky and had many slaves and many stores throughout the state. He was a grandson of Sir Thomas Owens, of Wales, of historic fame and my grandmother was of German descent. Small in stature but executive, she took full charge of the plantation in my grandfather's absence which was most of the time. She was the head of her household as well. Everything came under her capable control. She was the mother of twelve children. All grew to maturity, married and went on giving vigorous sons and daughters to the young and growing republic.

My grandfather Damron was of equal worth. He was a noted Indian fighter. He was employed by the government as a scout and spy during the wars with the Shawnees and Delawares. He performed many deeds of bravery and daring. He killed that noted Indian terror "Big Foot." He shot him in "Cumberland Pass;" but the most daring feat of bravery was his rescue of a mother and her five children from a band of Shawnees. For this the government presented him with a silver mounted rifle valued at three hundred dollars. Grandmother Damron was of Irish descent and noted for her great beauty.

My father was a tall, athletic Kentuckian, served as sheriff of Pike county for many years, was appointed as deputy at sixteen. It was said of him, "Tom Owens was not afraid of man or devil." Mother was of slight build but of perfect form. She weighed ninety-six when married at sixteen. Mother inherited her father's courage and bravery. She was the mother of twelve children and lived to have passed her four score years and ten (ninety). Brother Flem was my constant companion. He grew rapidly and soon overtook me in size; but I was tough and active. Not until I was twelve did he ever succeed in throwing me. One day he came in with a broad grin on his good-natured face and said, " 'Pop' told me to go to the barn for two bundles of oats for the horses. Now the first one down will go for the oats." Instantly the dish cloth was dropped and we clinched. I had noticed for some time that he had been gaining on me but I could not take a "dair" and he had not yet thrown me. Round and round the room we went, bending and swaying like two young saplings, till seeing his chance he put out his foot and tripped me. I fell and my mouth struck on the post of a chair which broke off a piece of one of my front teeth. Poor brother picked up the fragment of tooth, burst out crying and ran off for the oats. He had just learned this new accomplishment in wrestling which he had kept secret from me to his life-long regret, for in those times and parts dentistry was almost an unknown art. It was eighteen years before I could find a dentist who could repair the injury. Dr. Hatch, of Portland, did the work for ten dollars. I was more than glad to have the ugly gap filled with shining gold. It remained for thirty-five years and was perfect when extracted. I have saved it for a souvenir in remembrance of that particular tussle with my good brother, not the last by any means. We were constant companions and I was a veritable "tom-boy" and gloried in the fact.

It was the regret of my life up to the age of thirty-five years that I was not born a boy, for I realized early in life that a girl was hampered and hemmed in on all sides, simply by the accident of sex. Brother and I were always trying our muscular strength. and while in my thirteenth year I bet him I could carry four sacks of flour, two hundred pounds. We placed two sacks on & table and two on a box and I stood between. Brother placed a sack on each of my shoulders and then I managed to get the remaining sacks, one under each arm. Then while he steadied the two on my shoulders. I walked off triumphantly with the four sacks.

In the year 1847 after the Whitman massacre, my father was preparing to go with the Clatsop volunteers to fight the Indians. When all was ready and father stood in the midst of his weeping wife and children, a Mr. McDonald, who was working for father, stepped forward and said, "Mr. Owens. I am a simple man! I have no one to care for me but I am poor. Give me your outfit and money for my expenses and I will go in your place." Yielding at last to the entreaties of his family, father finally consented and Mr. McDonald went in his place, but he never returned. He was killed. We have always remembered him gratefully, believing he might have saved our father's life. At least he gave his own freely.

I was the family nurse and it was seldom I did not have a child in my arms and more clinging to me, when there was a baby every two years. There was no end to nursing, especially when mother's time was occupied from early dawn till late at night with inside and outside work, she seldom had time to devote to baby except to give it the breast. When the weather was fine we fairly lived outdoors, I hauling baby in its rude little sled or cart, which bumped along and often bumped baby out but which seldom seriously hurt and never killed. With a two-year-old on my hip and a four-year-old clinging to me to keep up or more often on brother Flem's back we went playing here and working there during all the pleasant weather. When it rained we ran to the barn where we could swing, play hide and-seek and slide down the hay mow. Many times I have carried the children to the top and with baby in my arms and the other two clinging to me we would slide to the bottom, to the great delight of all.

I was fond of hunting hens' nests and usually found them. One afternoon I crawled under the barn. I knew there were eggs there. The ground was hard and smooth, and near the barn floor, about the center. I found a nest full of eggs. I squeezed under so I could reach and gather them in my apron. I could not turn around so I began to slide out backwards, when passing a sleeper a knot caught between the waistband of my dress and the first button. Try as best I might I could not get loose. Brother was waiting outside and when he found I could not extricate myself he ran for mother. Father was away from home and mother knew the only way to release me was to break the button hole. Lying there on my face, wedged in, I could not reach the button or break the button hole. The big barn was full of hay which would have taken several men at least a day or more to get down to the middle of the barn and to have tunneled under would have taken as much time. Mother told me to push myself forwards, sideways and backwards, with all my force. After a long time I succeeded in tearing out the buttonhole. As soon as I got clear of the sleeper I reached back and unbuttoned all my buttons to make sure I did not get hung up again. Now being free, I soon backed out to freedom, bringing my eggs with me. That was not the last time I crawled under the barn for eggs; but, I had learned a lesson and I never went into a tight place like that again without preparing myself to leave all my clothes behind, in case I got hung up on a knot or peg.

When I was twelve years old, a teacher came to teach a three months school for our neighborhood. His name was Beaufort. School-books were very scarce. Sometimes whole families were taught from one book. All children over four attended school. Children did not remain babies long in those days, when other children came so fast to crowd them out of the cradle. Boys and girls of fourteen and fifteen were expected to do a full day's work on the farm or in the house, and the younger ones were taught to be helpful and to take care of themselves. The teacher was a fine, handsome young man. He kept himself clean and neat and trim and did not seek the company of the young men of his age. and they naturally disliked him. He boarded at our house and we children walked two miles to school with him daily. He was very kind to the children and they were all very fond of him. He would often take two or three little tots or as many as could hold on to him and then run races with the larger ones, to the great delight of the youngsters who thought they had won the race. I simply worshiped my handsome teacher who taught me so many things. He taught me to run, to jump, to lasso and to spring upon the horses backs, all of which I greatly appreciated.

One time there was a picnic at our house, it being the largest and best house on Clatsop. The young men began to joke and guy our teacher about his white hands. He took it good-naturedly, but finally said, "I will bet you two-hundred in cash, my watch and chain and all I have against one hundred and whatever you can put up, that I can dig, measure, and stack more potatoes than any man on Clatsop. This stirred their blood and touched their pride and they accepted his challenge. He was to dig, measure and stack, sixty bushels of potatoes in three stacks in ten hours, he to select the ground. My father said to Lagrand Hill who was then working for him and whom I married two years later, "My boy, take my advice and don't fool your summer's work away! I have been watching that young man for three months. He is as strong as a bear and as active as a cat;" but like the others, he needed no advice. He bet his watch and two hundred sheaves of oats on the issue. Mr. Beaufort selected Mr. Jewett's potato patch, near the county road. The day before he staked off the ground and smoothed off the spots on which to pile his potatoes. The day was bright and beautiful. Everybody was there, including Indians. It was a genuine picnic. Everybody came provided to stay all day and see the fun. The hour being near at hand, the teacher removed his coat, vest and long blue handsome Spanish silk scarf and hung them on the fence. Suspenders were unknown in those days. He then loosened his leather belt and taking off his boots he encased his feet in a pair of handsome beaded moccasins, then drawing on a pair of soft buckskin gloves over his soft white hands, he picked up the new hoe from which he had sawed off about half the handle and stepped to the middle of the plot. When the time keeper called the hour, he took off his hat and made a graceful bow, and stepping across a potato hill, with a foot on each side of it. with two or three strokes of the hoe he laid bare (he potatoes and with both hands scooped them into the half bushel measure. It did not require more than two or three hills to fill the measure. Then with two or three elastic leaps he emptied it on one of the places. For two or three hours he kept the tellers busy, then he took it easy and laughed and joked as he worked, and finished long before night. That was a red letter day for our handsome teacher. He had raked in watches, rings, scarf-pins and about all the spare money the young men and some of the old ones had. After he had finished he turned several hand springs and when he reached the fence, he put his hands on the top rail and sprang over and that was a revolution in potato digging on Clatsop. All the whites dug with a long-handled hoe and the Indians used a stick or their hands, crawling along on their hands and knees. That was a good lesson to the Clatsopites. He left in a few days and we never heard of him again, but his memory is always fresh in my mind.

He was in my young, crude and barren life, a green, flower-strewn oasis, with a fountain of cool water in its midst. I was but twelve years old, small, perfect in form, health and vigor. Brother Flem towered far above me and sister Diana, "The Clatsop beauty," was taller than our mother. My love of my handsome teacher knew no bounds. Sister Diana said I was always tagging him around and mother scolded me saying, "You ought to know that he must get tired of you and the children sometimes." But I found many opportunities of being in his society and I always improved them, especially as mother was so overworked and she was glad to be relieved of the care of the baby and two younger ones. Taking my brood, I would seek out my friend who invariably met us with a welcoming smile for he had learned to love the two tiny girls and the big fat baby, who returned his affection. He would catch up one of the older ones, toss her above his head in such a way that she would rest across his shoulders with little arms around his head and then he would take baby and hug her up, and taking the other tot under his arm we would be off for a race and how we did enjoy it. The children would scream with delight and my own happiness was no less deep. Often we went to the field where father was cultivating or ploughing, and many times did he lift me lightly to the back of the near horse and. handing me the baby and seating one of the others behind me. with one on this shoulder he would walk beside with his hand upon us to keep us from falling. Father liked him too, and was always glad to have him with us. It was a sad day when he left us. First he bade father and mother good-bye and then the children. He snatched up the baby from the floor, tossed her up and kissed her. I was trying to keep back my tears. He smiled down on me with his handsome blue eyes and said to mother. "I guess I'll take this one with me!" Mother said. "All right, she is such a tom-boy, I can never make a girl of her anyway." He took my little hand in his and I went some distance down the road with him. Then ho said, "Now little one, you must go back. You are a nice little girl. Some day you will make a fine woman; but you must remember and study your book hard and when you get to be a woman everybody will love you, and don't forget jour teacher, will you?" He gathered me up in his arms smiling and kissed me and then set me down with my face toward home. I ran back and seeing the children on the fence looking, I ran around back of the house in the garden and hid and cried a long time. Of course they all laughed at me and oftentimes when I was rebellious and wayward, which was frequent, I would be confronted with, "I wish the teacher had taken you with him," to which I never failed to answer promptly and fervently, "I wish he had too."

About this time a Mr. and Mrs. McCrary moved in on the adjoining farm. Their little home was just beyond a pretty little grassy hill, not more than a quarter of a mile away. I did not like the man but I fell in love with his tall splendid wife. She was older than my mother and very different from her. She was tall and fair but not pretty in form or face; but she was one of the most beautiful and admirable characters I ever met. To me she was beautiful, for I loved her always. No child could have loved a mother more than I loved this pure, noble woman. It is said that love begets love, and surely it did in this case for she returned my love with a true mother love. She was not blessed with children of her own. This affection remained unbroken through her long, subsequent life of nearly fifty years, and now looking back I can realize that the lovely example of her beautiful life has had much in molding my own and I doubt not that of many of the characters of those around her. They had but two small rooms, scantily furnished, but everything was immaculate and she with her hair combed smoothly back, her white kerchief pinned smoothly over her bosom and with her kind words, sweet smiles and sweet and winning ways, was a fitting and charming mistress of her spotless, little home. My mother was a neat and tasteful woman; but she said Mrs. McCrary always looked like she came out of a bandbox.

I always managed to visit my friend once a day and often several times. Whatever might be my task, I would finish it as soon as possible that I might slip off and fly to Mrs. McCrary's. It did seem like flying for my feet scarcely touched the ground as I ran. I received many scoldings for running off, and was told that grown up people did not want to be bothered with children; but unless I was positively forbidden, I went. She always seemed so glad to see me and had so many pretty and pleasant things to say to me that it was no wonder I loved her. She seldom visited and never gossiped. She was a reader, but books and papers were scarce in those days. She always treated me as if I was a little lady. She would say, "Your visits are just like bright, sparkling, refreshing sunbeams to me." If a button was gone from my dress or apron, a pin went in and she would say, "Now that looks so much nicer." Sometimes she would say, "I am going to comb out those lovely braids of yours." She would take down my hair, which came half-way to the floor, and then the little glass from the wall, holding it that 1 might see how pretty it looked, waving over my shoulders, saying, "We will just wait a while, it makes you look so like a fairy." Sometimes she told me fairy stories while she taught me to knit, crochet and sew, all this time talking and drawing me out, correcting my mistakes, with such delicacy, that my super-sensitive nature was never wounded. She infused such a charm into everything she did and said, that I was not only interested, but anxious to learn. She impressed upon my mind in the most positive language just how the things should be done and snowing me by example, and having me assist when possible and always excusing my blunders. If she was making biscuits, she would have me stand by while she showed me every step. "Now you take so many cups of flour, so many cups of milk, so much butter, so much salt and sugar for so many persons and when you knead the biscuits, be sure and do not get the flour too near the edge of the board or it will get on the floor and you must stand a little back, or you will soil your apron. Do you know I have seen women who would wear an apron all the week and then it would not be as mussed as that of some women would be in one day. Some women have a place for everything and keep them in place while some women keep their things haphazard and never know where anything is. They make themselves a great deal of work, and have a harder time. You will never be that kind of a person, for your mother is a good house-keeper." Was it any wonder that I loved that wise, good woman? I was as wax in her hands. Could I have been under her influence till I reached maturity instead of one year, I could and would have escaped many hardships and sorrows of my life.

After many years I returned to Clatsop and heard that Mr. McCrary was dead and Mrs. McCrary was spending the winter in Astoria. I went at once to see her. Oh, what a joyful meeting was ours and with what interest and emotion did we recall and rehearse the past. She was the same grand woman. Hardships and griefs of which she had suffered many, seemed to have made her more lovely and saintly. She said, "Well. I am getting old and you are young and fresh with the bloom and beauty of womanhood upon you; but I can see much to remind me of the little barefooted girl who brought me so much pleasure the year I lived near your fathers'." and she laughed heartily. Again we parted and years came and went. I became a physician, married, and went to live on my "Sunnymead" farm, on Clatsop. One dark night a messenger came with a lantern saying. "Mrs. McCrary is suffering dreadfully with an abscess. Would I go?" "Yes. by every fond recollection, by every tie of gratitude and affection, yes, I will go." A walk of a mile and a half over the rough roadless tide land brought us to the Lewis and Clark river where horses were awaiting us, then a three mile ride brought us to our destination. I administered an opiate and lanced the ulcer, applied a hot poultice and hot water bag and she was soon comfortable. Then she said, "How good God is to send you to me In my troubles. I do not regret my suffering so that it brought you to me. Now I want you to get right in bed with me. I am ashamed to be so selfish not to let you sleep in another room after such a hard trip; but if you had given me a bushel of opiates, I could not sleep. I am so hungry for a good long talk." "Do not think you are depriving me of anything, for I am as anxious as you for such a talk," and we did talk from 2 A. M. to breakfast time, living over much of our past lives from my early childhood. A few years later she came to Clatsop to visit friends who owned my father's old donation land claim. While there she was attacked with pneumonia and for a time I despaired of her life. She calmly said, "I know my time has come! I am ready and anxious to go. I have lived beyond my usefulness! You are doing all you can and I do not blame you; but I feel that I ought to go now." But her time was not come. She recovered and went to Portland to live with her adopted son whom she had raised from infancy. I saw her there frequently.

In 1899, just before moving to Yakima, Washington, I called to say good-bye. On seeing me she arose to her feet and met me with her heart warming smile. "I see you are reading the Oregonian," I said. "Yes, I spend much of my time in reading. If I could only remember what I read. My memory is just about half across the floor. You see that is about the length of it." "Never mind your present memory," I said, "your past will not desert you, and the good you have done in this world will linger long after you and I have been laid to rest." The pleasant and cheerful way in which she alluded to her loss of memory illustrates the wonderful charm and beauty in which she invested life, so that all its rough, unsightly and annoying features were sure, under her sunny way of presenting them, to become less disagreeable and often charming. To me her examples have been helps and blessings throughout my life. That was the last time I saw that grand, noble woman, one of God's masterpieces. Her walk in life was lowly; but sunshine and flowers followed her and illumined her pathway. No one came in contact with her without being made better.

An amusing occurrence took place when I was about thirteen. Father had a little, ugly Welshman working for him. This man had been trying to make love to me for some time and notwithstanding my scornful rejection of his attention and positive rude treatment of him he persisted. One morning I was washing. In the room under the stairway were several barrels half-filled with cranberries. That little imp, knowing I was there and watching his opportunity, slipped up behind me as I was stirring down the clothes with a long broom handle. He threw his arms around me and hugged me and tried to kiss me, then jumped back and laughed triumphantly and tried to escape by the open door; but like a tiger I leaped between him and the door and gave him such a whack with the broom handle that he staggered and rushed under the stairs and plunged his head in the cranberry barrel, thus presenting a fair field for the strokes which in my fury I laid on thick and fast with all the strength I possessed. He screamed and mother hearing the disturbance ran down stairs and had to actually pull me off by main strength. When I got his head out of the barrel he sputtered and stammered and could not utter a coherent word. In towering contempt I exclaimed, "You little skunk, if you ever dare to come near me again, I'll kill you."

About this time another occurrence happened that made a lasting impression on my mind. One morning a young farmer about twenty-seven years old came rushing excitedly up with his coat on his arm to mother who was in the back yard, saying, "Where is Tom Owens?" "What do you want of him? He is not here." "I want him and I intend to whip him within an inch of his life." Mother said, "Now Luke, go home and get over your mad fit. Owens has never done you any harm and I tell you now, if you do get him roused he will beat you half to death, and I don't want to see you hurt;" but he had no notion of getting hurt. Just then we saw father coming up the road on horseback. Luke saw him and started for him. Mother called and begged him to come back, the children were terribly frightened and began to cry. Mother said, "Stop your crying, your father is not going to be hurt." She walked out with us to where we could see and hear all. Father stopped his horse, and Luke, throwing down his coat, began gesticulating, swearing and daring father to fight him; but father sat calmly on his horse and said, "Now Luke, you are only a boy, and you don't know what you are doing. Go home and let me alone. I don't want to hurt you." At this Luke sprang at him, calling him a coward and attempted to pull him off his horse; but before he could catch his foot, father was off his horse on the opposite side. Giving the bridle a pull he turned the horse away from him. The first thing he did when Luke came lunging at him was to knock him down with a single blow and then he held him down and choked him till he cried enough, when father released him saying, "Go to the house and wash and clean yourself up! My wife will give you water and towels." Luke lost no time in obeying and mother assisted him. She said, "I am very sorry you did not take my advice for I knew you would get hurt." He was very penitent and humiliated and when father came up. bringing his coat and assisted him in putting it on. they shook hands and were friends ever after. It turned out that some of the neighbors knowing him to be a bragging bully and wanting to see the conceit taken out of him had told him that father had accused him of stealing.

In 1853, finding that his six hundred and forty acres could no longer supply food for his rapidly increasing herds, father decided to move to southern Oregon. He set about building a flat boat or scow in which to move the family and stock that he did not wish to sell. In the fall, after the crops were harvested, and everything sold that was not desirable to move, the stock was shipped to Rainier and then the family and teams were shipped to Portland, then a small town. After disposing of the boat and loading up the two wagons we started for the valley. It had been raining and we had a terrible time getting through the timber, west and south of Portland, father leading and mother following with the second team.

Mr. John Hobson, my brother-in-law, had taken the cattle and horses through by a trail and leaving them in care of the men came back and met us in the woods for which we were very thankful. We came up with the herd and bidding Mr. Hobson and the men good-bye we proceeded on to Roseburg, without mishap, brother Flem and I with one man, who father said was not worth half as much as either of us. Father said we were worth more as drivers than any two men he could hire. The weather was fine and there was plenty of grass. That part of the journey was a picnic. Upon leaving home I insisted upon taking my big cat, "Tab," against the judgment of everybody; but after a good deal of argument and many tears on my part, I carried my point. After well on our way I let him out after making camp, putting him in the covered wagon and fastening down the cover. When we were ready to start one morning the horses had strayed off and father sent me after them. When I returned with them everything was packed and was moving. I forgot Tab. After going a mile or more I thought of him and rushed back to mother's wagon. She had not seen or thought of him. Without a word I put whip to my horse and galloped back to camp and rode up and down that pretty little creek calling, "Tabby"; but saw no signs of him. With a sad heart I rode back and overtook the wagons and stock. When we stopped for noon mother sent me to the wagon for something and when I lilted the cover what did I see but my big. beautiful Tab, ready to meet me with his affectionate meow. On reaching Roseburg we found our old friends, the Perrys, who had a house ready for us and we moved in. Father took up a claim just across the Umpqua river from the little town of Roseburg. He bought lumber for a good house und began hauling it on the building spot, lie had a large scope of range and during the winter he built a ferry boat for his own Accommodation and the public.

During the winter Mr. Hill came to visit us. His family had come to Oregon the year before and settled in Rogue River valley. It was arranged that we should be married in the spring when father's house was ready to move in. During the winter and spring I put in all my spare time preparing for my marriage. I had four quilts pieced. Mother gave me lining for all and cotton for two and I carded wool for two and we quilted them all. She gave me muslin for two sets of sheets and pillow cases, two table cloths and four towels. I cut and made two calico dresses for myself and assisted her with my wedding dress which was of pretty sky-blue lawn. Mr. Hill came in April and assisted us in moving into our new house. On the 4th of May, with only our old friends, the Perrys, and minister besides our family, we were married. I was still very small. My husband was five feet and eleven inches and I could stand under his outstretched arm. I grew slowly until I was twenty-five. Am now five feet and four inches. Just prior to our marriage, Mr. Hill had bought a farm of three hundred and sixty acres, four miles from father's, bought on credit for six hundred dollars to be paid in two years. The improvements consisted of a little log-cabin, twelve by fourteen, without floor or chimney. The roof was made of boards tied on with poles. One window consisted of two panes of glass, a section of log sawed out. Later I chinked the cracks with grass and mud. About ten acres had been fenced and seeded to oats and wheat. A rough open shed sufficed to shelter six or eight cattle. Our furniture consisted of the pioneer bedstead, made by boring three holes in the wall in one corner and then one leg was all that was required. The table was a mere shelf fastened to the wall. Three small shelves supplied for a cupboard and were sufficient for my small supply of dishes. My cooking utensils were a pot, bake-oven, frying pan and coffee pot. A washtub and board and a large pot for washing and a full supply of groceries I got on my father's account as he told me to go to the store and get what I wanted. He also gave me a fine saddle mare, Queen, a fresh cow and calf and a heifer that would be fresh. Mother gave me a feather bed and pair of blankets. My husband's possessions consisted of.a horse and gun and less than twenty dollars in money. The Hon. John Hobson had once said to me, ''Your father could make money faster than any man I ever knew. He came to Clatsop with fifty cents in his pocket and I don't think there were one hundred in the county, and in ten years he was worth twenty thousand," so I had high hopes and great expectations. My husband was strong and healthy. I had been bred to thrift and economy and everything looked beautiful and bright to me. My soul overflowed with love and joy and my buoyant and happy nature enabled me to enjoy everything, even to cooking outdoors without a shelter over my head.

Soon after our marriage father urged my husband to begin at once to fell trees and hew them so as to put up a good house before winter; but he was never in a hurry to get down to work. He frittered away the whole summer in going to camp meetings, reading novels and hunting. In September when the mornings and evenings grew cold we bought an old second-handed stove which we set up in one corner of the cabin. This was a great comfort to me. Soon after this we had a heavy rain. The next morning our house was flooded, and in one corner the water was bubbling up. That was from a gopher hole. It was late in November before the logs were even ready to be hauled for the sixteen by twenty house. Father provided doors, windows, shingles, nails and lumber for floors. He had all on the ground long before the logs were ready. At last all was ready and father came with men to help raise the house and mother came bringing bread, pies and cakes to help me with the dinner. The house was soon up and the openings for the windows and door were sawed out. Father said, "Now Lagrand, go right at it and get the roof on, for we can look for a big storm soon." Next morning I slipped out of bed and milked the cow and had breakfast almost ready when I tickled my husband's feet to get him in a good humor, because he was not pleased at what father had said. At breakfast I said, "Now we have an early start and we will show father how soon we can get the roof on and the floor down." I was so excited over the prospects of having a fine new house with a floor arid windows. By the time the roof was on Mr. Hill was getting tired and suggested a hunt, but I begged and coaxed for only half the floor so we could move in, till he reluctantly went ahead. When sufficient floor was down for our one-legged bedstead it was moved in and made up and then one of my new braided rugs went down. No young wife of wealth could have looked with more pride on her velvet or Turkish rugs than I did on mine that I had made from scraps. When half the floor was down Mr. Hill stopped to put in the door and mashed his finger which meant a lay-off for a time. November was nearly gone. The cooking must be done in the old hut. There was no opening for the pipe and not sufficient pipe. I was planning to get the pipe with the butter and few eggs I could save the next week. Our groceries had all been bought with the butter except what mother gave me. Winter was on us and we were in a dilemma. I realized our condition. Though but fifteen I knew that it was due to the want of industry. He suggested that we go to father's for a visit. I did not like that for I .realized that father did not approve of shiftlessness, but I had to consent for he had begun to exhibit temper when I objected to his plans. We got up the horses, nailed up the house and taking our cow and calf we took ourselves to fathers. There we stayed for two weeks, then father got us a box of groceries and stove pipe and he and mother came over and helped us get settled and now with two cows we could get along.

Mr. Hill had been receiving letters from his folks who were doing well and urged us to sell out and come out there in the spring. In April we were to pay three hundred dollars on the farm and we had not a dollar. Nothing had been added to or taken from the place excepting the house and father had furnished everything except the bare logs. Mr. Hill was handy with tools and could have had work all the time at good wages. The owner was anxious to get the place back and offered sixty dollars to have it returned, so we decided to go early in the spring. We traded the younger calf and crop for another horse as 1 would have to ride Queen to drive the cows. We remained several months with his father and mother and then he decided to go to Yreka, California, so he sold my cows and now that he had money he suggested that we ride back and see my folks before we went so far away. I was homesick and glad to go. Father did not approve of his having sold my cows. He said, "Now take my advice and settle down, and remember it does not take long for a few cows to grow into money." Mr. Hill had an aunt in Yreka. As soon as she heard we were there she came to see us. She had partly raised him. She said, "Now Lagrand, you must get right into work. There is plenty of it at good wages; but you must not leave this little wife alone. There are too many rough men here. She will be safe with me and I can help you both so you pick up and move right over to my house." 1 was delighted and she proved to be one of the best of mothers to me. She was an executive woman. She had two cows, and chickens. She sold milk, eggs and made cakes and pies for sale and took in sewing and so we worked together, she giving me all and more than I earned. "Now, I am going to see that you have plenty of nice clothes and I shall see to it that you do not give it to Lagrand to fool away." He sold the team and wagon. She would say, "Now. Lagrand, I want you to buy a house and lot while you have the money." In March there was a lot and a small one-roomed battered house with a barn, too, for sale for four hundred and fifty dollars, which we bought just across the street from Aunt Kelly's, which was a bargain. We paid three hundred dollars down, which was all the money left from my cows, heifer and team. My Queen was out on pasture which was now a bone of contention as she was only an expense; but I refused to have her sold and Aunt Kelly stood by me. We moved in and on April 17 our baby was born and Aunt Kelly begged me to give him to her. She would say, "Now, Bethenia, you just give him to me and I will educate him and make him my heir. I know Lagrand will just fool around all his life and never do anything." I continued to work for Aunt Kelly who was overworked and by this means I was able to keep up the house.

Mr. Hill did not drink or use tobacco but as his aunt said he simply idled away his time, doing a day's work now and then, spending more than he made. Father had heard how things were going. Thus the time dragged on till September. 1857. when one day father and mother drove up, to our surprise. They came to see the country and baby. It did not take them long to see that we were living from hand to mouth. "How would you like to go back to Roseburg? It is a growing town. I have several acres and I will give you an acre and lumber for a good house which you can build this fall." We were delighted and sold our house for less than a hundred dollars profit and were soon packed and on our migration. My only regret was leaving dear Aunt Kelly who had taught me so many useful things. With many tears I bid her goodby. The weather was fine and we enjoyed the trip till we came to a deep gulch with a high, narrow bridge. Mother sat on the back seat with my youngest sister in her lap. I sat beside my husband. Father' was leading Queen behind. The moment we were across Mr. Hill started up the horses with the whip, to which they were unaccustomed on a hill. In springing forward the wheel came up against a rock, and in the attempt to bring them around they began to back. I saw the danger and with one bound I was on the ground with baby in my arms. Laying him on the ground I seized a chunk, and turning I saw father running and heard his commanding shout. "Whoe!" The next instant he had seized the spokes of the wheel and with one supreme effort he stopped the wheel at the very edge of that forty-foot gulch. Meantime I had placed the chunk back of the front wheel and thus an awful tragedy was averted. Not till the danger was passed did I realize that I was hurt. I had suffered a severe sprain of my right foot which caused me suffering at times for many years.

Upon reaching home father said, "Go over and select your acre and your building spot." which I gladly did. Then he told Mr. Hill to take the team and he and the boys could haul the lumber, which they did; but Mr. Hill had been talking to a man about making brick. The man had the land and the teams. Each was to furnish a man and I should cook for them for the use of the team. Father begged him not to attempt it as the ground had not been tested and it was too late to burn a kiln; but the more he talked the more he was determined to put all we had in the venture. So he moved me down in the low, swampy place in a tent and we began work. But before a hundred brick were moulded it began to rain and put a stop to the work and I was stricken down with typhoid fever. Father and mother came with the wagon and took us home. It was now late in November and winter had set in. When I became convalescent, father urged him to begin on the house. He replied that he wanted a deed to the acre before he began the house. Father told him that he and mother had talked it over and had decided to deed the property to me and the boy; that they had given us one good start and now after three and one-half years we had nothing left but one horse. This enraged him and he said that he would not build on the acre unless it was deeded to him as he was the head of the family. Father asked him to think it over and not act rashly. He sulked for a time then bargained for a lot and hired a team and hauled the lumber off the acre to the lot and began to build. All this time we were living off father and mother who said nothing but furnished shingles and told him to get the nails on their account. In time the house was up and the roof on and floor down and kitchen partly finished. It was so open that the skunks made night hideous by racing under and on the floor and even getting on the table. My health was poor and baby was fretful and ill most of the time and things were going anything but smoothly.

A short time before the climax came I went home and told my parents that I did not think that I could stand it much longer. Mother was indignant and told me to come home, "that a man who could not make a living with the good start he had never would, and with his temper he is likely to kill you or the baby." But father broke down and said, "Oh, Bethenia, there never has been a divorce in my family and I hope there never will be. Go back and do your best to get along, but if you cannot possibly get along come home." I went back relieved for I knew I could go home. Our troubles usually started over the baby. He was so cross and had a voracious appetite. His father thought he was old enough to be spanked which I could not endure and war ensued and I received the chastisement. The evening before the separation he fed the child six hard boiled eggs in spite of all I could say or do. I did not close my eyes that night expecting the child would go into convulsions. Early in the morning early in March after a tempestuous scene he threw the baby on the bed and rushed down town. As soon as he was out of sight I put on my hat and shawl and taking baby I flew over to father's. I found brother Flem ferrying a man over and I went back with him. By that time I was almost in a state of collapse. I had run all the way, about three-fourths of a mile. Brother seeing that something was wrong and always anxious to smooth out the wrinkles, said with a smile, "Give me that little 'piggy-wig.' and shall I take you under my other arm? It seems to me you are getting smaller every year. Now hang on to me and I will get you up the hill all right. Mother will have breakfast ready and I guess a good square meal is what you need." The next day father saw Mr. Hill. He found he had been trying to sell the house. He told him that he would come with me to get my clothes and a few things and he could have the rest. As the lot was not paid for the house would go with it, and when he sold it I would sign the deed. Before he found a purchaser he repented and came several times to get me to go back. I said, "I have told you many times if I ever left you I would never go back and I never will." And now at eighteen l found myself broken in health and spirit again in my father's home from which four years ago I had gone so happy and full of hope. It seemed I should never be happy or strong again.

At this time I could not read or write legibly. I realized my position fully and determined to meet it bravely. Sorrow ended with cheerfulness and affection and nourishing food. My health soon returned and with it an increasing desire for education. My little George felt the benefits as much as I. He was such a tiny mite that he was only a plaything for the whole family. I said one day, "Mother do you think I might manage to go to school?" "Why, yes. Go right along. George is no trouble. The children will take care of him." From that day I was up early and out to the barn, milking and doing all the work possible. Saturdays with the help of the children I did the washing and ironing for the family. At the end of four months I had finished the third reader and had made good progress with the other studies. In September, Mr. and Mrs. Hobson (sister Diana), came to visit us, and she begged me to go home with them. With a light wagon and good horses we had a delightful trip over the road where I had helped to drive the stock five years before. Before going father had me apply for a divorce, the custody of my child and to change my name to Owens. The next spring brother Flem met us at Salem with a light rig and took us home in time for the May term of court. The suit was strongly contested on account of Mr. Hill's widowed mother, who wanted the child, thinking that would induce her son to remain with her on her farm as all her children had homes of their own. I, however, won the suit.

Now the world began to look brighter to me. I was a free woman. I sought work in all directions, even washing, which was the most profitable in those days. Father objected to this and said, "Why can't you be contented to stay at home? I am able to support you and your child." But no argument could shake my determination to support myself and child. So he bought me a sewing machine, the first one ever brought to that part of the country and so with sewing and nursing a year passed very profitably. Now my sister, Mrs. Hobson, urged me to return to her on the farm on Clatsop. She greatly needed my help. In the fall of 1860 she and I went to Oysterville, Washington, to visit an old friend, Mrs. Munson. The few days passed off too quickly and Captain and Mrs. Munson assured my sister that they would see that I reached home safely if I would only stay till I got my visit out. I told Mrs. Munson of my anxiety to go to school. She said, "Why not stay with me? We have a good school here, and I shall be glad to have you, especially further on." I said I would gladly accept if I could only find some way of earning my necessary expenses. She said, "There is my brother and his man. I can get their washing which will bring you in from one dollar to one dollar and a half per week. I gratefully accepted doing their washing evenings. Work to me was mere play and change of work is rest and I had plenty of it. Thus I passed one of the most pleasant and profitable winters of my life. Whetted with what it fed on, my thirst for knowledge grew stronger daily. My sister now urged me to go back to her. which I did. I said to her, "I am determined to get at least a common-school education. I know I can support myself and child and get an education, and I am resolved to do it. And I do not intend to make it over the wash tub, either. Neither will I work for my board and clothes. You need me and I will stay with you six months if you will send me to Astoria to school next winter." She agreed to that. Later I said, "Diana, don't you think I might teach a little summer school? I could be up at four to help milk and have the other work done by 8 A. M., and I can do the churning, washing and ironing evenings and Saturdays." She said, "You might try it." I asked Mr. Hobson if he would not get me up a little school. He said, "Take the horse and go around among the neighbors and work it up yourself." I lost no time and got the promise of sixteen scholars at two dollars each for three months. This was my first attempt. I taught my school in the first Presbyterian church in Oregon. Of my sixteen scholars there were three further advanced than myself, but I took their books home and with my brother-in-law I kept ahead of them, and they never suspected my incompetency.

Fall found me settled in an old hotel in Astoria in one small room. I had to take care of my nephew and my George. And now I encountered one of the sharpest trials of my life. On being examined in mental arithmetic I was placed in the primary class. Words cannot express my humiliation at being required to recite with children eight and ten years old. This was of short duration, for with the teacher's assistance I was soon advanced to the second class and then to the third, the highest. At the end of the nine months I had passed into most of the advanced classes, not because of ability but by determination and hard work. At 4 A. M. my light was burning. I never allowed myself more than eight hours for sleep. I permitted nothing to come between me and this, the greatest opportunity of my life. Next summer I was on the farm, milking, butter-making and doing all kinds of work on the farm. It was now 1862 and the state called upon the counties to contribute to the "Boys in Blue." Clatsop, being a dairy district, decided to contribute a mammoth cheese. Mr. Hobson had a man who made cheese so he and I volunteered to make the cheese. Everybody contributed milk; the ends of a hogshead were sawed off and the middle was used for a hoop. After the cheese was made the hoops were filed off. The cheese was pronounced a success, and was sold and resold in Astoria and brought one hundred and forty-five dollars. I was then sent with it to the state fair where it was again auctioned on" many times till it brought between four hundred and five hundred dollars, and then the money and cheese were forwarded to the Oregon soldiers. Whether they found it palatable or digestible I never learned, as such things were not as easily accounted for as now. In the fall I rented three rooms in Astoria and with scanty furniture which I procured by the proceeds from blueberry picking and other work, I set up housekeeping. I was eager for school but my expenses must be met and this is how it was done. I engaged to do the washing for two large families, and washing and ironing for one. Sunday night found George and I at Capt. C.'s. At 4 A. M. I was in the kitchen. George went to school with the children and at 10 I was there myself. Monday and Tuesday this was repeated. The other was done at my rooms. For all this I received five dollars per week, including the kindest of treatment. This was sufficient to provide for our wants, especially as we lived on the beach, which enabled us to pick up most of our wood. And thus I was happy in my independence. At that time there was a kind and estimable man in Astoria, a Captain Farnsworth. He was a friend of Mr. and Mrs. Hobson. He knew of my struggles for an education. One rainy evening he called. George had been tucked in bed and I was ironing at the table with my book before me. Thus I studied while I worked. My hands were trained to do their part without calling upon the brain. Removing his heavy overcoat and seating himself by the table he said, "Have you no time to talk?" "Oh, yes; I can talk and work, too." "Well," he said, "I want you to put away that work. I have come to talk to you and I want you to listen well to what I have to say." I closed the book, folded the ironing cloth and sat down, not knowing what was coming, but feeling very apprehensive. He saw this and smiling, said, "Don't you ever get tired?" "Oh, yes; but I get rested easily and quickly." 'How long do you expect to go on this way?" "I don't know," I said. "I don't want to see you working in this way, and I have come to see you as a friend, and I want to be a true friend to you. I am alone in the world. The nearest friend I have is a nephew. I have more money than I need and I think I cannot do better than to help you." Trembling, and with moist eyes I exclaimed, "No, no; I cannot take money from you!" "Now, don't be foolish, but listen to me. I know you are thinking that it will compromise you. Besides you are a great deal too independent for your own good. I am a good deal older than you and know vastly more of the world than you do, and I want you to understand that if you accept the offer you are never to feel under any obligation to me. My offer is this: You are to select any school in the United States for as long a time as you choose. I will furnish the money for all the expenses for yourself and boy and no one shall ever know from me where the money came from. If you say so I will not even write to you." Could there ever have been a more generous or unselfish offer? I was now in tears, but my self will, independence and inexperience decided me to refuse it. I could not consent to such an obligation. The acceptance of that offer would doubtless have changed my whole life, but who can tell for better or for worse. Captain Farnsworth was thoroughly disgusted at my obstinacy, though he was still my friend, yet he did not show the same interest in me from that time and many times in after years during my hardships and struggles in my supreme efforts to get ahead, I bitterly repented my hasty decision, feeling that it was the mistake of my life.

Others beside my generous friend, the Captain, had been watching my efforts. Colonel Taylor and Mr. Ingalls were the school directors, and as the wife of the principal was prevented from assisting they generously gave me the position at a salary of twentyfive dollars per month for the remaining three months. This was a wave of prosperity, and as one good thing sometimes follows another l was offered board and room for myself and George for the care of nine rooms in a private boarding house, which I accepted. I asked and received permission to recite in two advanced classes. I also joined a reading and singing class which met once a week. When I was given charge of the primary department I had among my pupils a young lady who was far ahead of me when I attended the Oysterville school. Before the school closed I received a call to teach a three months' school at Bruceport, Washington, at twenty-five dollars per month and board. Judge Olney was county school superintendent. With fear and trembling I applied for an examination. He said, "I know you are competent to teach that school. [ have had my eye on you for a year, and I know you will do your duty. I will send you a certificate," and he did. This was great encouragement, and made me more determined to do my best.

I accepted the school and left with my boy as soon as my school closed, and opened the Bruceport school at once. After two weeks a collection was taken up among the oyster men and a few families for a second term, and before the six months closed I had a call to teach the Oysterville school, which had the undesirable reputation of being ungovernable. It was my reputation for good government that had prompted the directors to offer me the school. My reply was, "I will engage to teach your school if the directors will pledge their support to my government." They did, and I taught the school. There were three students that made all the trouble - a girl and two boys. The girl was the ringleader. About the third day one of the boys stuck a pin in the girl. I reprimanded him and told him to bring his lunch the next day and stay in noontime. He only groaned. The next day he failed to show up and in the afternoon his older brother came dragging him in. I met him at the door and taking him by the hand attempted to lead him to his seat. He had on heavy shoes and kicked me vigorously. That was a little more than my temper could stand. I seized him by the shoulders and fairly churned the bench with him, which subdued the young gentleman in short order. At the close of the school I gave him his choice of staying in during noon hour for one week or receiving five blows on each hand with the ferrule. He chose the latter and 1 administered the punishment at once. The Irish girl was living with one of the directors. He told me that she came running home and said, "It's no use fooling with that teacher; she don't scarce worth a cent." She was twelve and proved to be one of my best scholars both in Behavior and aptitude. That was the only punishment administered in that school by me. Before the close of that school I received a call for a four months' school on Clatsop at forty dollars per month and board myself. With my boy I moved into the old parsonage at Skipenon which had been unoccupied for a long time. This I could have free, so that with the addition of a few boards and nails made two rooms comfortable for spring and summer, so I was happy as a lark. I was an expert, as experts went in those days, with the sewing machine and crochet needle and my hands were never idle. I had in this way, so tar, saved all my school money, and with this term I would have four hundred dollars. My ambition was to have a home. I had bought a half lot and engaged a carpenter to build me a little three-room house with a pretty little porch. To this, my last school, I can look back with pleasure and satisfaction. The neighbors and farmers were kindness itself to me. At the end of the term I moved in my little home. How proud I was! I could turn my hand to most anything and work came from all directions.

During all these years Mr. Hill kept on writing, urging me to remarry him. One dark night while my machine was buzzing and I was singing while I sewed, a knock came. I opened the door and there stood the father of my child. He had come unannounced, thinking his appearance might overcome my opposition. But, alas! He did not find the young inexperienced child-mother he had abused, but a full-grown, self-reliant and self-supporting woman who could look upon him only with pity. He now realized that there was a gulf between us which he could never hope to cross. He said, "Can I come and take my boy down town with me tomorrow ? I will not ask you to wake him up tonight." "You can if you will promise not to run off with him as you are always threatening." "I will promise." Not daring to trust him I hastened to the sheriff next morning and told him my troubles. He smiled and said, "Now don't you worry, my dear little woman. He will never get out of this town with that child."

In the fall I rented my little home and went to Roseburg to visit my people at their urgent request. Roseburg was growing and they urged me to stay and go into business, so I rented a house and opened a millinery and dressmaking establishment. For two years I applied myself, and saved my earnings and bought my home and had a good, growing business. My boy was in school and work brings its reward and pleasure and I was happy. 5 A. M. never saw me in bed. Yes, I had had two years of uninterrupted success, but now a new milliner made her advent and opened next door to me. She came right in and looked me over, stock and all. She said she had been a milliner for years, had learned the trade and understood it thoroughly, and had come to stay. I was soon made to feel her power. She laughed and ridiculed my pretentions. Said mine was only a picked up business. She knew how to bleach and make over all kinds of straw. She could make hat blocks on which she could make over hats and frames, all of which was Greek to me. She came late in the fall and her husband went all over the country picking up all the old hats and advertising his wife's skill. This was not only humiliating to me, but also a severe blow to my business. I was at my wit's end to know what to do and how to do it. One beautiful day I was thinking the matter over while eating my dinner in front of a window which overlooked my neighbor's kitchen. I had seen her husband unload several boxes of old hats the evening before and now they were getting ready for bleaching and pressing. They sat at a table out in the sun on which they placed two new plaster paris hat blocks and now the work began not twenty feet from me. My house was above them and I could see them and hear everything they said; but they could not see me. For an hour I sat there and learned the art of cleaning, stiffening, shaping, pressing and bleaching. Oh, what a revolution. My heart was beating fast and I felt that I had never learned so much in one hour in my life. I saw how easy it was and how much profit there was in it. I knew if I could get the blocks I could press the hats so I stepped down and asked her what she would charge for two blocks. She said, "Thirty dollars." "I will think of it: I did not expect them to be so high." "You do not expect me to give my business away." Then with a smile she said, "Can you press hats?" I passed out and as the door closed I heard them laughing. This roused me and I said to myself, "The day will come when I will show you that I can press hats and do several other things as well. First of all I will find out how to make hat blocks. I had a book "Inquire Within." From this I learned how to mix plaster of paris. My first attempt was a failure, but it proved I was on the right track. 1 slept little that night, but I had thought it all out. As soon as the drug store was opened I bought a dollar's worth of plaster paris and in less than one hour I had made my coveted block. Words could not have expressed my triumph. In less than twenty-four hours I had found and held the key to that mysterious knowledge that had charmed away my customers. I commenced at once to put my acquired knowledge into practice and resolved not to allow a soul to know how I had obtained it. The next day a lady brought me a fine old hat to be renewed. "Oh, you haven't got any of that beautiful lace fringe. Mrs. has it! Would you mind getting it?" "Not at all." When the hat was ready, I wrapped it carefully and walked into my rival's store with the pride of a full grown peacock. Laying it on the counter and lifting a pressed hat from the block that she kept for an advertisement on the same style. I asked. How much of the bugle lace will it take for this hat?" "Three-quarters of a yard." I laid down seventy-five cents, she measured it off. "Please stick a pin in and I will see if it is enough," unwrapping the hat and measuring with the lace. As I finished I clipped it off with my belt scissors and dropped it in my hat. "Whose hat is that?" "It is one I have just made over for a customer." "Who pressed it?" "I did." "Who made the block?" "I made it myself," I said, and I walked out. I heard no laughing then. She knew I had her secret, but never knew how I obtained it.

I put my newly acquired knowledge into practice. All winter I worked. My work and goods were equal to hers; still the customers passed me by and bought of her. She managed to checkmate me. Thus the summer wore away and left me stranded, but not conquered. My time had not been lost and I knew I had gained much that would be of service to me in the future. I had surmounted other difficulties and I would jet wring victory out of this defeat. I had learned more of human nature than 1 had ever known. I saw that I must convince the community that I was not a pretender but was in reality mistress of my business and that could not be done by making over old hats and bonnets.

In November, of 1869, I left my boy with a minister and his wife who occupied my house, borrowed two hundred and fifty dollars and left for San Francisco, having previously advertised in the paper that I would pend the winter in the best millinery establishment for the purpose of perfecting myself in the work and would return in the spring bringing the latest and most attractive millinery. I carried that out to the letter. I sent out posters. Had a grand opening and swamped my rival and she left in disgust. I cleared one thousand, five hundred dollars that year and business continued to increase as long as I conducted it. In 1870 I placed my son in the University of California. I had a love for nursing. Mother said I was born a doctor, was always feeding the rag dolls with a spoon. Now my time was beginning to be encroached upon by calls from friends and doctors. One evening I was called by a friend. The old doctor came and was trying to catheterize her poor, suffering little girl by his bungling attempt. He had lacerated her tender flesh. At last he laid down the instrument to wipe his glasses. I picked it up and said, "Let me try, doctor," and passed it instantly with perfect ease, bringing instant relief. Her mother, who was in agony at the sight of her child's agony, threw her arms around my neck and sobbed out her thanks. Not so. the doctor. He was displeased and showed his displeasure most emphatically. A few days later I called on my friend, Dr. Hamilton, confided to him my ambitions and asked for the loan of medical books. As I came out of his private office in his drug store. I saw Hon. S. F. Chadwick, who had heard the conversation. He came up, shook me warmly by the hand, saying, "Go ahead. It is in you. Let it come out. You will win." The Hon. Jesse Applegate, my dear father's friend, who fondled me as a baby, was the only other one who ever gave me one word of encouragement. Realizing the opposition, especially from my own family, I decided not to mention my plans. I began at once to arrange my business affairs so that I could leave in eighteen months. I worked and studied as best I could. In due time I announced my decision. I had expected opposition, but I was not prepared for the storm of opposition. My family felt that they were disgraced and even my own child was made to think that I was doing him an irreparable injury. Most of my friends seemed to think it was their Christian duty to try to prevent me from taking the fatal step. That crucial fortnight was a period in my life never to be forgotten. I was literally kept on the rack. I had provided a home for my now seventeen year old boy in Portland.

My business, all in good shape, was entrusted to a sister who had been with me for a year. The day I left two friends came to say goodby. One said, "Well, this beats all! I always did think you were a smart woman, but you must have gone stark crazy to leave such a business and run off on a wild goose chase." I smiled. "You may change your mind when I come back a physician and charge you more than I have for hats and bonnets." "Not much. You are a good milliner; but I'll never have a woman doctor about me." Choking back the tears, I replied, "Well, time will tell." As a fact both of those ladies receive my professional services, and we laugh together over that goodby conversation. 11 P. M. came at last and found me seated in the California Overland stage beginning my long journey across the continent. It was a dark and stormy night and I was the only inside passenger. I was alone with my thoughts. I realized that I was starting out into an untried world alone with only my unaided resources to carry me through. All rose up before and all that I had left behind tugged at my heart strings. My crushed and overwrought soul cried out for sympathy and forced me to give vent to my pent up feelings in a flood of tears, while the stage floundered on through a flood of mud and slush and the rain came down in torrents as if sympathizing nature were weeping a fitting accompaniment to my lonely, sorrowful mood. I had time to reflect. I remembered that every sorrow of my life had proved a blessing in disguise and had brought me renewed strength and courage. I had taken the step and I would never turn back. Those cheering words from my faithful attorney came to me then as a sweet solace to my wounded spirit. "Go ahead. It is in you. Let it come out. You will win." How many times have those inspiring words cheered me on through the dark hours of my life. I resolved that if there was anything in me it should come out and come what might I would succeed. That decision comforted me.

Upon reaching Philadelphia I matriculated in the Eclectic Medical School and employed a private tutor. I also attended the lectures and clinics in the great Blockly Hospital. In due time I received my degree and returned to Roseburg. A few days later an old man without funds died and the five doctors decided to hold an autopsy. When they met, Dr. Palmer, who remembered my impudence in using his catheter, made a motion to invite the new Philadelphia doctor. This was carried, and a messenger was sent for me with a written invitation. I knew this meant no honor for me, but said, "Give my compliments to the doctors and say I will be up soon." The messenger left and I followed close behind and waited outside till he went in and closed the door. He said, "She said to give you her compliments and she will be up in a minute." Then came a roar of laughter. I opened the door and walked in, went forward and shook hands with Dr. Hoover who advanced to meet me and said, "The operation is to be on the genital organs." I answered, "One part of the human body should be as sacred to a physician as another." Dr. Palmer stepped back and said, "I object to a woman being present at a male autopsy. If she is allowed to remain I will retire." "I came by written invitation and I will leave it to a vote whether I go or stay; but first I will ask Dr. Palmer the difference between a woman attending a male autopsy and a man attending a female autopsy?" Dr. Hoover said, "I voted for you to come and I'll stick to it." No. 2, "1 voted yes and I'll not go back on it," and "So did I." Dr. Hamilton said, "I did not vote, but I have no objections." Dr. P., "Then I'll retire," which he did, amid the cheers of forty or fifty men and boys.

Inside of the old shed the corpse lay on a board, resting on two old saw bucks, wrapped in his old gray blankets. One of the doctors came forward and offered me an old dissecting case. "You do not want me to do the work, do you?" "Oh, yes; go ahead." I took the case and complied. The news of what was being done had spread to every house in town. The excitement was at fever heat. When I had finished, the crowd, not the doctors, gave me three cheers. When I passed out and down to my home the street was lined with men, women and children, anxious to get a look at the terrible creature. The women were shocked and scandalized, and the men were disgusted and some amused at the good joke on the doctors. Now that I look back I believe that all that saved me from a coat of tar and feathers was my brothers, Flem and Josiah. They did not approve of my actions any more than others; but they would have died in their tracks before allowing me to suffer such indignities, which that community well knew. I did not at the time stop to consider the consequences. I was prompted by my natural disposition to resent an insult, which I knew was intended. I closed up my business as soon as possible and taking my sister moved to Portland and opened my office. I frankly admit that I breathed more freely after I had bid adieu to my family and few remaining friends, and was aboard "the train, for it did seem that I was only a thorn in their flesh; but I will say right here that that affair was the means of bringing me many patients, especially from that locality, in after years, which added much to my purse and reputation.

For four years I practiced and got ahead far better than I had expected. I had given my sister a course in Mills Seminary; my son a medical education and set him up in business. I had eight thousand dollars at interest. I was thirsting for more knowledge. The old school would not recognize the Eclectic School, which was a thorn in my flesh. I said, "I will treat myself to a full course in Allopathy and a trip to Europe. Again my family and friends objected; saying, "You will soon be rich. What do you want to spend all you have got for?" But I was deaf to all entreaties. I must and would drink at the fountain head. This time I armed myself with letters from governors, senators and professors, and on September 1, 1878, I sailed for San Francisco. In due time I matriculated in the University of Michigan. After arriving there I was in my seat the next day but one. During the next nine months I spent sixteen hours a day excepting Sundays, in attending lectures, clinics, quizzes, and hard study. During vacation I spent ten hours a day in hard study. Most of the time was given to Professor Ford's question book on Anatomy, which was a "bugbear" for medical students. This book contained only questions and covered Gray's Anatomy from beginning to end. I completed it except a few answers which I could not find. When the term began I took it to Prof. Ford to get the answers. He took the book and examined it carefully. "And you have done this? You have done what no other student of this university has done and I never expected them to do, and you have done it while they have been enjoying a vacation, and I shall not forget it. It will be of great value to you in the saving of time and fixing the facts in your mind."

It was my custom to rise at 4, take a cold bath, then exercise, then study till breakfast, at seven. I allowed myself one half hour for each meal between lectures, clinics, quizzes, and laboratory work, two good sermons on Sunday, now and then a church social, the time was fully and pleasantly occupied. The constant change brought rest and acted as a safety valve to my overheated brain. At the end of two years I received my degree and sent for my son, and with him and two lady physicians sailed for Europe. My letters with state seals always secured us open doors as travel was not then as it is now. We were there for study and we received the benefits by visiting the great hospitals and medical schools of the countries through which we traveled and attended their clinics. While in Munich we were being shown the masterpieces in castings. The guide opened the door and ushered us into a large circular room known as the American Department. The central figure was a heroic statue of Washington on his great white charger, carrying the flag of his country. Around him were grouped the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and there was our martyred Lincoln striking the fetters from the "black man. I hat sight, so beautiful, so real, so moving was enough to stir the blood of the coldest American. For months I had not seen "Old Glory," and her bursting upon our view, floating over all, the images of all we held nearest and dearest on earth was too much for my impulsive nature. Forgetting time and place and oblivious to all around me I rushed forward and fell upon my knees at the foot of the "Father of His Country " and gave vent to my pent up feelings of joy in exclamations of "Oh, My Country My Country, My Flag." I was brought suddenly to my senses by the warning voice of Dr Hill. "Mother! Mother! These people cannot understand one word of English and no telling what kind of trouble you will get us into." I sprang to my feet looking behind me expecting to see the gendarmes coming to take charge of me. Instead I saw a picture I shall never forget. The door was filled with great, broad, smiling faces, showing more plainly than words that they thoroughly understood the situation and heartily sympathized with the loyal American. As we passed out they further showed their appreciation and approval by bows and smiles. Dr. Hill said, after passing out, "Well I never did see anything like it. Mother is always getting into scrapes but somehow she always comes out on top."

Dr. Hill became homesick before the trip was nearly ended, declaring he would rather go home to his sweetheart than to see all the countries in the world. I gave him five hundred dollars and his return ticket and he lost no time in getting back to Goldendale and getting married. Upon reaching London I found many letters, one from a dear friend, begging me to come to her. I like Dr. Hill was homesick. Three years was a long time. When I landed in New York the custom collector demanded seventy-five dollars on my surgical instruments which I purchased in Paris. I said, "I am a physician and these are for my own use. Here "are letters from United States senators, governors, doctors, and the president of the University of Michigan. If you take my instruments I will employ a lawyer." He said. "You sit , right here. You will have to pay that duty." He was gone two hours. He" said, "Take your things and go on!" I speedily obeyed, glad to get out of his clutches. In a few hours I was on my way to San Francisco. On reaching Portland, I found a carriage waiting to take me to the bedside of a patient, as all passengers names were telegraphed ahead. That was surely an auspicious beginning. I was delighted to get home and to get to work. My purse was depleted. I had but two hundred dollars left. Within twenty-four hours I had secured nice rooms over my old friend's. Dr. Plummer's drug store. A few days later a doctor whom 1 had known and greatly admired called upon me. His home was in Roseburg. He said, "I cannot succeed in Portland. I am going to sell at auction. I have many things you will need. Come to the sale?" "Why doctor, 1 have just come home. I have no money." "No matter, you can have everything I have without a dollar. You will soon earn enough." "But I do not know that." "I do! I only wish I was sure I could make half as much. In less than six months you will be making six hundred a month." I was astonished for I knew he was in earnest and yet his prophesy came true. I had for so many years been struggling, clinging to the slippery ladder and fighting for an existence making headway surely but so slowly that I could not realize that there was so much within my reach.